The image was created with the help of Microsoft Designer

This piece has been originally posted on Medium.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “consultant” as a “one who consults another.”

How true! As someone who’s been in the consulting business for many years — as a consultant and also as a consumer of consulting services — let me assure you that this is exactly what consultants do: they share their knowledge and experience with other people.

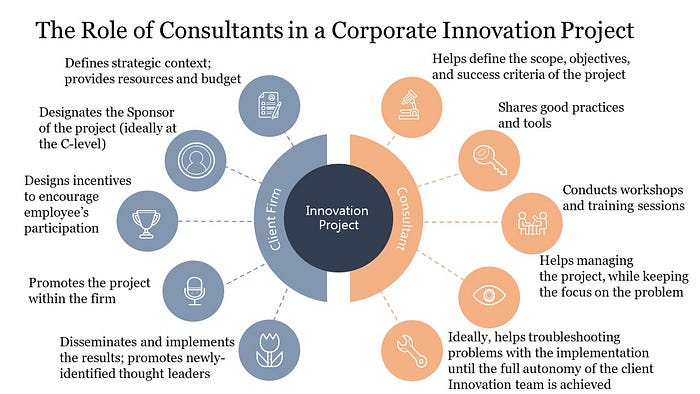

This knowledge and experience can take different forms and in the picture below, I attempted to summarize the roles that consultants may play in the corporate innovation process:

One can wonder perhaps: consultants are usually outsiders who often have a poor knowledge of what’s going on inside the firm. How can they teach insiders?

First of all, as the great Sherlock Holmes once said, “If you have all the details of a thousand [misdeeds] at your fingertips, it is odd if you can’t unravel the thousand and first.” Experienced consultants have seen enough different troubles in other firms — and how these troubles were resolved — that they almost always can suggest a right solution to this particular problem in this particular firm.

Besides, they have a certain edge over the insiders: consultants are not exposed to the often-toxic fumes of internal politics. This helps them better deal with competing ideas and opinions, judging them on their merits rather than their authorship.

And then, there is this ability to be a “stranger in the room,” a luxury of not knowing the ways things “have always been done here” — and being naïve enough to keep asking stubborn “why’s” when everyone else in the room already knows the “right” answer.

I appreciated the magic power of a “naïve” question a few years ago after having a meeting with a client, a pharmaceutical company.

As often happens, the meeting was organized in haste, and the only thing I was told was that the client wanted to discuss the issue of phosphorus-containing detergents. I thought I knew what that meant. This pharmaceutical company used phosphorus-containing detergents to clean production vessels after each manufacturing cycle. But phosphorus-containing compounds, notoriously environmentally unfriendly, had been steadily falling under regulatory scrutiny; it was only a matter of time before the regulatory authority, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, would ban using them altogether.

I knew from my previous interactions with this client that they wanted to act proactively and switch to detergents based on more environmentally safe organic acids, as some of their competitors had already done. Having assumed that the client wanted to crowdsource the optimal composition of a new cleaning solution, I spent my flight time reading relevant articles I managed to print out before rushing to the airport.

The next morning, I was sitting in a room with five managers responsible for cleaning the manufacturing equipment. A nice breakfast was served, and, judging from my prior visits, a delicious lunch was to follow by noon.

After a few minutes of discussing the latest football scores, I got down to business: “Okay guys, do you want to identify the best phosphorus-free cleaners?”

“No,” responded the gentleman in charge of the meeting on the client side, “there are plenty of commercially available cleaners based on citric acid. We know precisely what we want to use.”

I felt a bit puzzled: “So, what is the problem?”

“The problem is that there is a strong resistance inside the manufacturing unit to switching from a phosphorus-containing cleaner to the one based on citric acid. We tried, but it didn’t work.”

Feeling even more puzzled, I asked: “Who in the company has the authority to make this decision? Have you talked to this person?”

By the silence that followed, I realized that I had said something absolutely horrible. Completely unwillingly, I had put my hosts in an awkward situation: They should have felt embarrassed that such a simple — obvious even to a stranger — solution had somehow escaped their attention.

The managers exchanged uneasy glances, and the one in charge uttered: “Well, we don’t actually know…”

Another manager intervened to help: “We’ll find out and bring this issue to the table. Perhaps, the situation isn’t as bad as it appears…”

Barely in its fifteenth minute, our four-hour-long meeting was over. We chatted a bit more, discussing potential next steps, but I already knew that this team would never contact me again. (I was correct.) Apparently mindful of the fact that I was deprived of lunch, my hosts paid for my cab to the airport.

I managed to change my mid-afternoon flight for an earlier one and my watch was telling me that I would be home well before dinner. I sat in a half-empty airport terminal lit with the bright morning sun and sipped coffee from the nearby Starbucks.

Life was good.